0.03 Some Perils of Generalization

In recent years, it has become clear in the larger field of book history that readership studies, or more generally the history of the reception and use of printed books, resists generalization. Every early modern reader brought unique experiences to the individual copy he or she picked up. The reading each individual gave a book can sometimes be studied, but it can rarely be pronounced typical. This degree of variation obtained in the manuscript age and remained the case in the age of printing. The mass production of books does not mean that we have to do with a different kind of reading history. The invention of printing merely changed the history of some singular readings into a history of many, many singular readings, complicating the problem of generalization. (17) Educational publishing in the sixteenth century, then, must be understood to embrace numerous exceptions to the few apparent rules. Even in so narrowly defined a field, publishing ideals and practices varied greatly and progressed unevenly. From most modern points of view early modern publishers acted inconsistently, even erratically. Then too, some one hundred fifty different texts in well over two thousand different editions were produced in Italy during this period specifically for the use of teachers and students in the single area of Latin grammar. I cannot claim to have read all these texts or even to have seen them all, far less to have examined all the editions, sometimes many dozens, of individual texts. (18) Trying to account for every text or even most of them would give a picture so blurred as to be unreadable.

Still, some sorts of reading are easier to study than others and educational reading is one of them. (19) We can evaluate the meanings individual textbooks had when there were many editions in large print runs and when there are sources that allow us to describe the classrooms in which these books were used. Classroom use is by its nature less singular than private reading because it is the moment when groups of students are learning how to read, a skill they will employ life-long. As they grow intellectually readers employ these skills with increasing degrees of individualism. In the classroom they are more likely to act like each other. Thus, the classroom affords us a window on groups of readers, but it does not always give us a clear view. Textbook history is always limited because the evidence, overwhelmingly the textbooks themselves, cannot unambiguously reveal how those books were used. At best, Renaissance textbooks offer a limited view of how they were probably intended to be used.

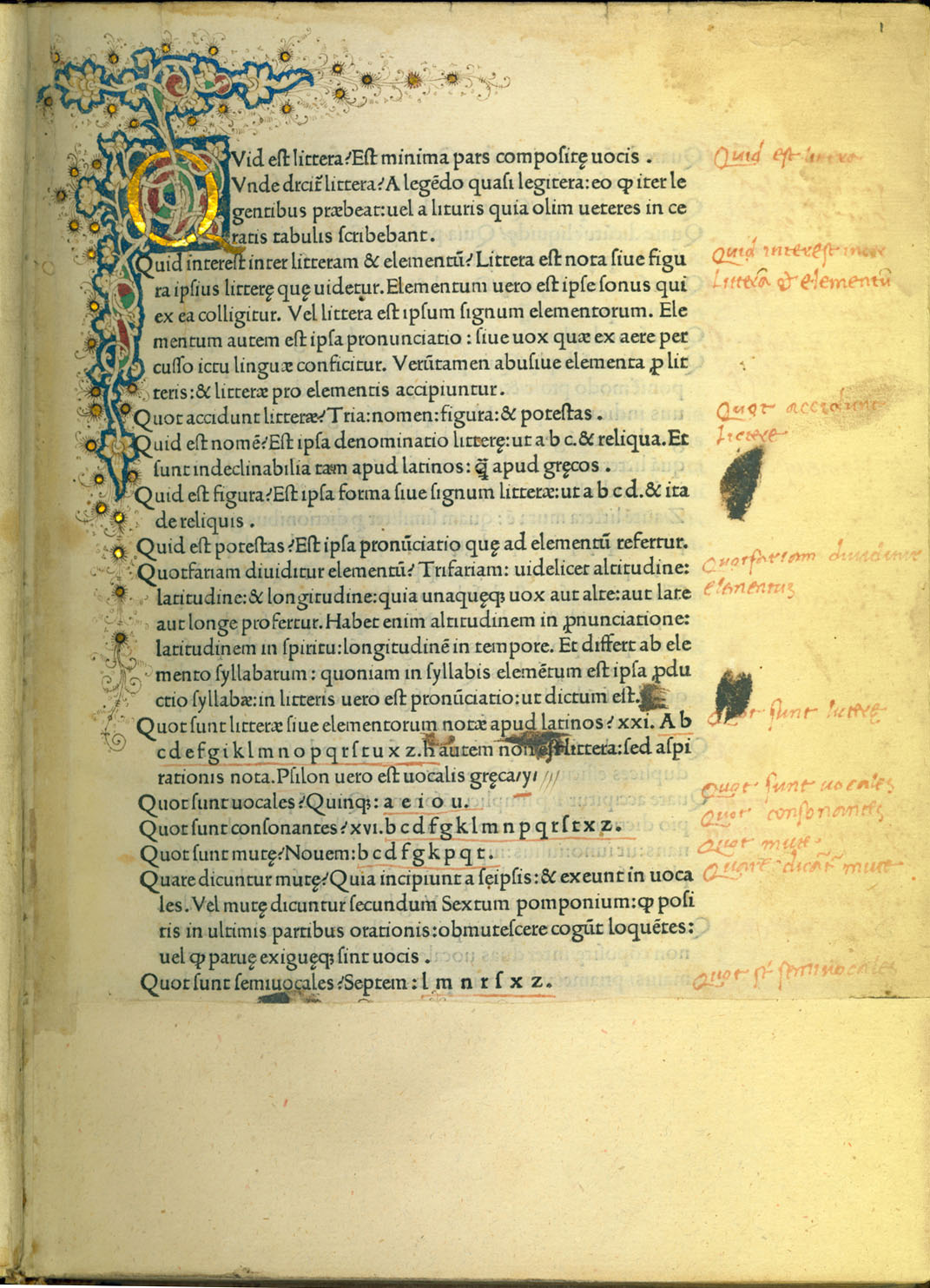

Another tricky problem concerns what evidence has come down to us and what is simply lost. Elementary textbooks, especially grammars and arithmetics, have a very low rate of survival. (20) A few telling examples will serve to measure the problem. We know that the most widely used basic Latin textbook in Renaissance Italy, the Donat (erroneously ascribed to the late ancient author Aelius Donatus), had many printings. Some thirty separate editions are known from fifteenth-century Italy, but only a few of these editions survive in more than a single copy. A similar rate of survival characterizes editions of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, with the added problem that catalogs and bibliographies for the later period are much less complete than for the fifteenth century. The rare survivors, our only evidence for the publishing history of this important and common text, are scattered in libraries across Europe and the Americas, and we will never know how many editions were made that do not come down to us at all.

By way of corollary, one innovative elementary textbook of the fifteenth century, a reworking of the Donat, purportedly by the Roman humanist Pomponio Leto (1428-1498), is known in a single copy of an edition apparently printed after the author's death. Leto's achievement remains a footnote in the history of humanist education because it had no practical effect on other writers or teachers. His little reform grammar was published, but it had no publishing history. (21) Another great humanist of Leto's time, Giorgio Valla (1447-1500), also wrote a Latin grammar, in this case a lengthy, systematic treatment which appeared in his posthumously published encyclopedia entitled A Work on Things to be Pursued and Those to be Avoided (1501). In 1514, the three books on grammar were excerpted from the larger work and published as a separate volume, ostensibly offered for school use. But there is no evidence it ever reached the hands of students. The book is very rare and we have no way of knowing why. Most likely it was printed speculatively in a small run and did not find enough of an audience to merit a reprint.

Still another methodological problem concerns terminology. Teachers and publishers in the long sixteenth century possessed no standard or uniform vocabulary with which to describe textbooks, a fact aggravated further by the humanist habit of looking for original, striking, or elegant expressions. Their titles could be grand or humble, largely without reference to the audience the author had in mind or the physical size or shape of the book. Even terms that would seem to indicate a specific kind of treatment or level of instruction can be deceiving. As a result it is often possible to judge the level of a given text and its intended audience only after a physical examination of multiple editions. (22)

For example, the Latin term rudimenta ought by every possible logic refer to a work for beginners. But the Rudimenta grammatices of Francesco Venturini (dates unknown) is a handsome, imposing folio of almost four hundred spaciously arranged pages. It was published only once, at Florence in 1482, and it is hard to understand how it was used without examining many copies for annotations and other signs of ownership and use.

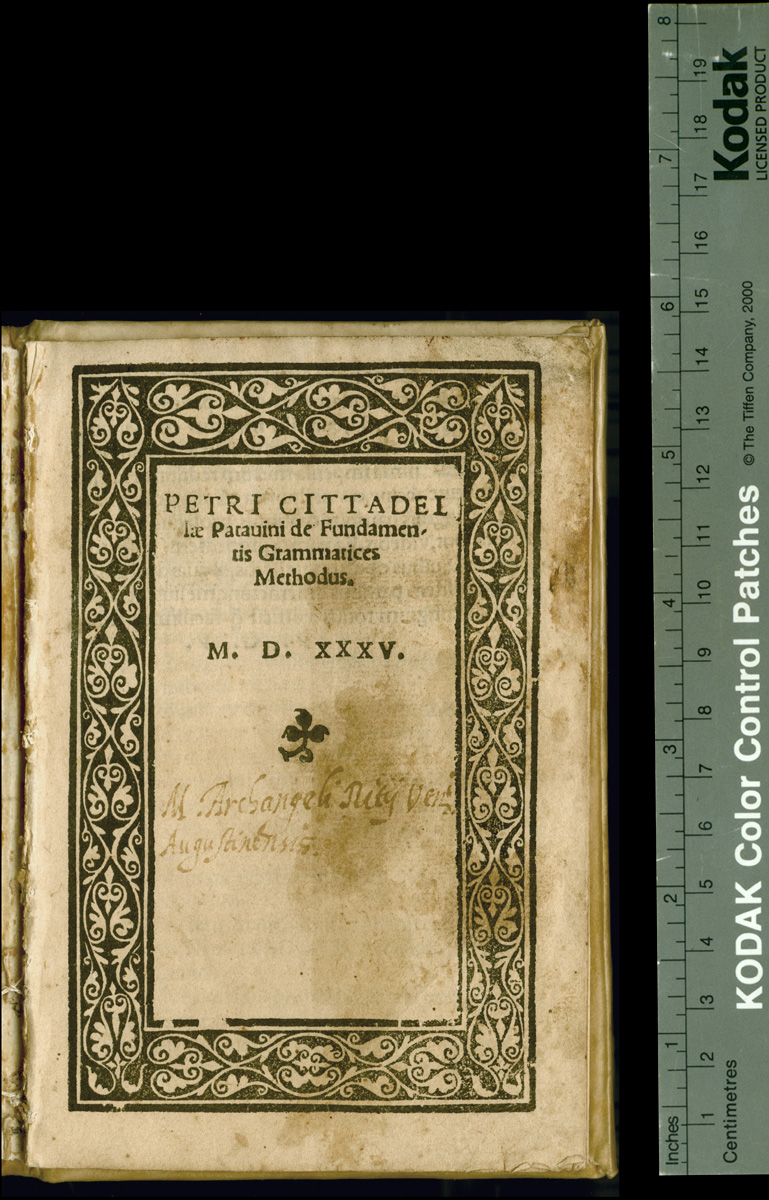

A comparable title might seem to be the De Fundamentis grammatices methodus of Pietro Cittadella (dates unknown), and it too was published only once, at Venice in 1535. But Cittadella's book runs to only forty pages in small octavo. It is so rare there is no real hope of comparing copies. There is almost no evidence of how it was used except the author's preface, which simply says it is an introductory work that will be followed by a longer and more detailed one, apparently never published. (23)

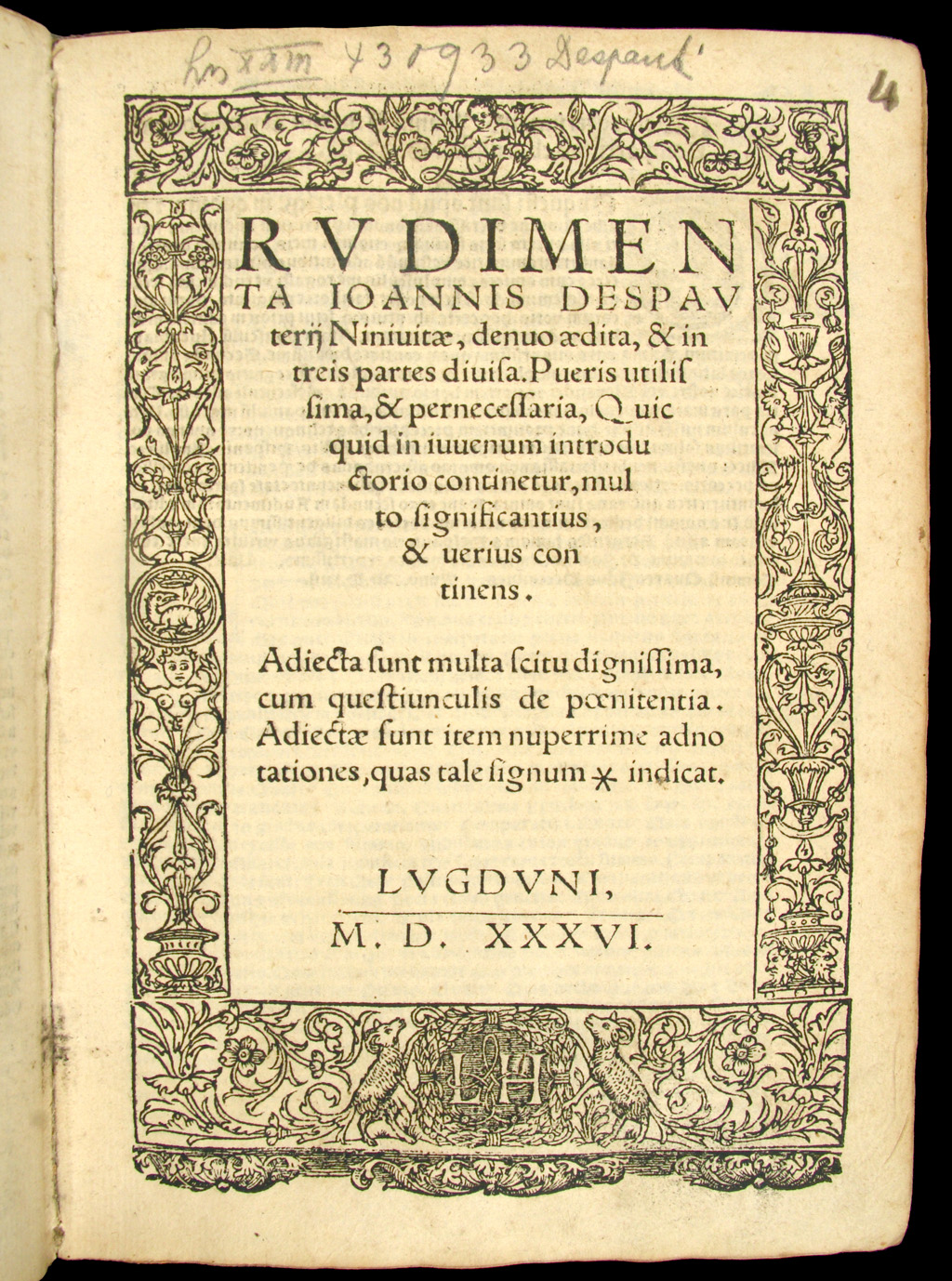

Again, the Rudimenta grammatices of Johannes De Spauter (ca. 1460-1520) is more like Cittadella's book than Venturini's, or so it would seem on first glance. It was usually presented in a single quarto-sized gathering of ten or twelve leaves, crowded with type in several sizes employed to specifications by De Spauter himself. It got many dozens of printings in this format between the first edition of 1514 and the end of the sixteenth century. Often it stood as the first work among several at the same basic level in collections. De Spauter was the most talked-about textbook author of his day, so we know a great deal about how the Rudimenta was used. But in 1537, Robert Estienne at Paris included the Rudimenta in a folio collected works of enormous dimensions for a textbook (nearly 33 cm.). The types are among the largest and most handsome of the French Renaissance. At that size and splendor it can only have been intended for a learned audience, or perhaps for a prosperous teacher with some ready cash. (24) This habit of dressing the same text in radically different forms persisted across our period.

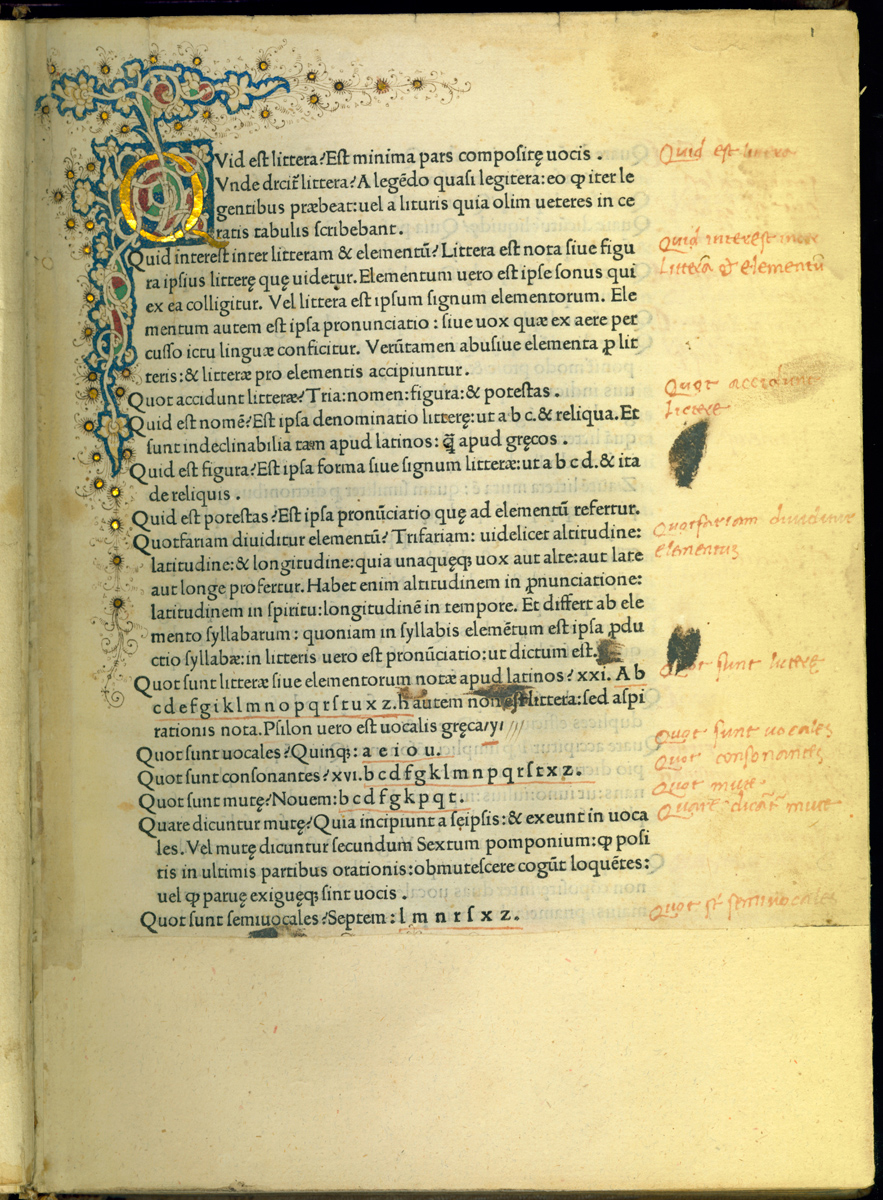

Another Rudimenta grammatices, that of Niccolo Perotti (1430-1480), started its long textbook life as a generous folio. Within a few decades it also got treatments in large and small quarto. Much later it appeared in octavo as well. Before it got its own octavo editions, however, Perotti's grammar was excerpted by a Florentine grammar master, Benedetto Ricardini (active around 1500). Ricardini's Erudimenta grammatices was one of the earliest grammars to appear in octavo. On its face, it appears to be a highly original basic grammar book advertised with Perotti's name. It turns out, on close examination, to be a pastiche of advice on Latin composition drawn from a dozen or more authors. (25) Obviously, it is necessary to see texts like Perotti's in a full variety of formats before generalizing about how they were used.

NOTES Open Bibliography (330 KB pdf) (17) Chartier 1987, 6-12, 183-197; McKenzie 1989, 89-90, 101-106; Wheatley 2000, 52-57; Pawley 2002, 143-160; Ruffini 2002, 144-147; Cormack and Mazzio 2005, 1-8. (18) The hundred-odd titles I have examined are listed in the bibliography, as a Short Title List of Editions Cited. (19) Milde 1988, 7-11; Chartier 1995, 83-90; McKenzie 2002, 201-209. (20) Jensen 2001, 104-105; Sandal 2006, 55-57. (21) This version of the Donat is discussed at greater length in sections 2.04 and 2.05. Leto also wrote a more general (and equally innovative) grammar published in 1484. It too had very limited influence; see Zabughin 1910, vol. 2, 208-223; Ruysschaert 1954. (22) Kirkenheim 1951, 54-55. (23) Cittadella 1535, fol. 1v. (24)  Hébrard 1983, 79-80; Colombat 1999, 37. (25) Ricardini 1510, apparently the only edition.