2.15 Printing the Cato

Unlike Ianua, the regional variant of the Donat Italians knew, the Cato text used in medieval and Renaissance Italy was much the same as the one used beyond the Alps. It circulated under the rubric Catonis Disticha because most of the proverbs it contained were two-line verses. There is no distinct Italian manuscript tradition; and the base texts in printed versions were much the same North and South of the Alps. Once the Cato text began to appear in elaborate editions with extensive annotations for teachers, it was common for these printed texts to cross the Alps, just as other scholarly books did. (90)

We have already noted, however, that in Italy Pseudo-Cato often circulated together with the Ianua in a single manuscript booklet subsumed under the name of the Donat. In the North the Ars minor of Aelius Donatus and the Cato were usually treated as separate texts both in manuscripts and in early printed versions. In origin, the Donat and the Cato had different roles in the curriculum, since Aelius Donatus wrote a book of grammatical rules (and the Italian Donat was an equivalent set of rules), while the Cato was offered as a first literary reader. This functional distinction was preserved in Northern European printed editions. In the North, the Cato was often paired with the fables of Avianus. (91) Both these texts also appeared in an anthology of medieval elementary reading texts that was partly standardized before the introduction of printing and which circulated widely in print as the Eight Authors (Auctores octo). Many of these same school texts circulated in medieval Italy too, but not in standardized collections. (92) With the exception of the Cato, they were slowly eliminated from the curriculum by humanist teachers for exactly the reasons cited by Bebel -- bad Latin and insufficient attention to simple, commonplace moral themes. None of them appeared with the Cato in printed Italian editions. Instead, humanist teachers continued to use the Cato together with or immediately after Pseudo-Donatus and then went on to more complex reading texts in parallel with an intermediate grammar book. This was the pattern on the eve of the invention of printing, and it continued into the seventeenth century. The Donat -- in the sense of Pseudo-Donatus plus Pseudo-Cato -- became the standard printed package in Italy for the first course in Latin. (93)

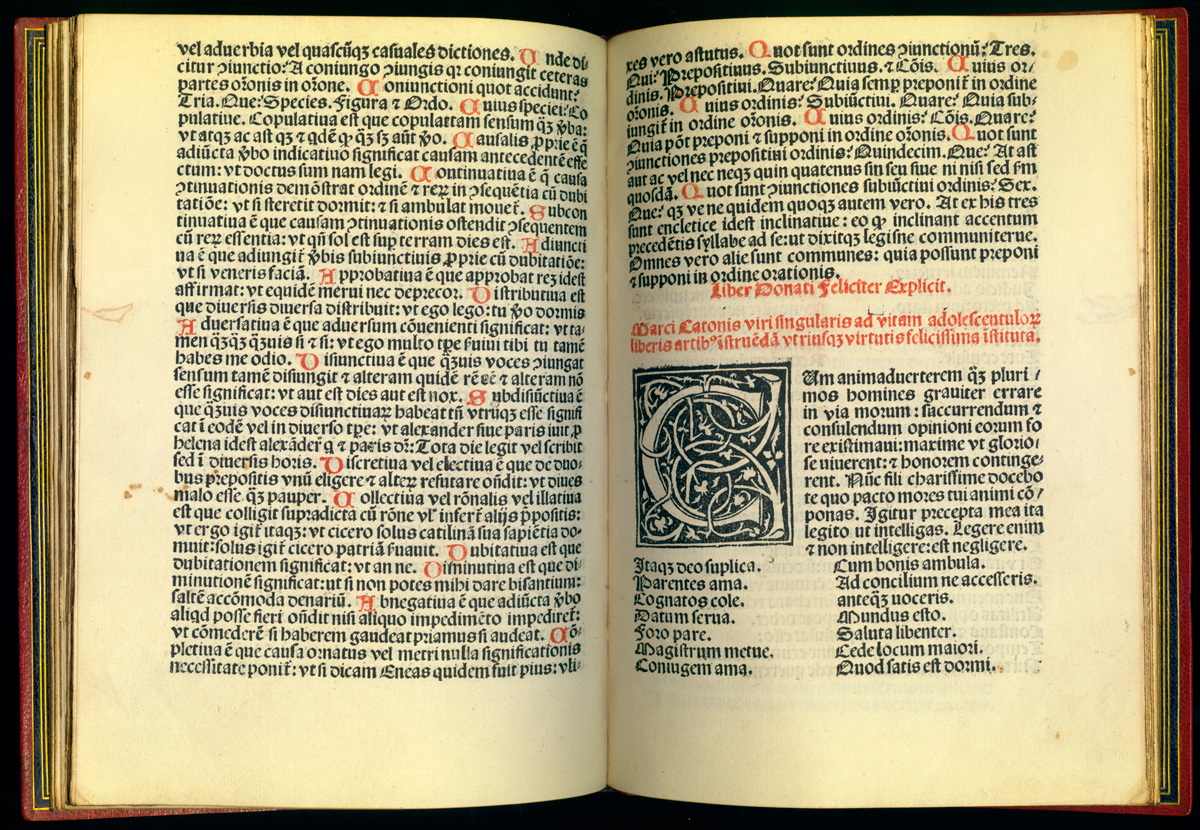

Because Pseudo-Cato and Pseudo-Donatus were so often used together in Italian schools, the typical Italian Cato is in fact just an appendix to a Donat. Entirely to pattern, for example, is the Cato that occupies nine and a half pages at the back of the pretty little Donat printed by Giovanni Battista Sessa in Venice around 1500. (94) The Ianua portion of the book is presented in colorful red and black print throughout; the Cato has only a few touches of red, most notably the two-line caption title which starts at the middle of page twenty three: "The most felicitous precepts of the remarkable Marcus Cato, for the instruction of young men of virtue in liberal arts." (95)

The printers employed a large round gothic type, and although the page is relatively crowded the text remains highly legible. The first forty-eight proverbs are very short and are arranged in two columns; the remaining aphorisms run to two lines of poetry each and are set in a single column.

The only additional ornaments to Pseudo-Cato are a large, white-stem initial C at the start and printer Sessa's mark (a cat and mouse) filling out the blank portion on the last leaf. Though well printed and charmingly designed, this book is utterly traditional. Except for the advertisement implied in the red title, it offered the unelaborated Pseudo-Cato text that had been used in Italy for as long as anyone could remember. Interestingly, we know that Sessa was also offering a bilingual Donato al senno during the same years, that is, a non-traditional version of the same texts both in Latin and in Italian. (96)

At the other end of book production for schools stands the fully annotated Cato printed in Venice by Giorgio Rusconi in 1518. This is a teacher's edition, in which the proverbs occupy not ten but 111 pages. The base text is set in small type and the notes for teachers are set even smaller. The Cato is one of three such traditional school texts in a 160-page booklet that was intended to stand at the front of a collected set of the works of Antonio Mancinelli. (97) The text of Pseudo-Cato was fixed by tradition; it is no longer here than in the pamphlet of 1500. The additional hundred pages contain a brief grammatical commentary by Mancinelli and much longer literary and moralizing notes by the editor, Josse Bade Ascensius. Between them, Mancinelli and Bade tried to imagine everything a teacher could possibly want to know or say to students about these texts. They routinely gave a paraphrase in natural (prose) word order of each proverb in poetry; and they supplied synonyms for unusual words. They pointed to problematic forms and indicate which ones are to be parsed in the classroom. Above all, they expanded on the moral meaning of each verse and

Josse Bade, editor of this and many other schoolbooks, is a particular case whose career outside Italy nonetheless influenced Italian textbook publishing considerably. Born near Brussels and trained at Louvain, he taught school in Lyon and then became a successful printer at Paris. His commentary on the Distichs of Cato was a very thoroughgoing one, concentrating on the philological issues of vocabulary, inflectional form, and literary parallels. It was first printed at Lyon as part of a large compendium of moral texts and commentaries called Sylvae morales in 1492 by Bade's father-in-law, Jean Trechsel. It was re-issued as a separate in 1505 and 1517 by other printers, and in 1518, as we have seen, as part of the Venice collected edition of the works of Antonio Mancinelli. Finally Bade reprinted it partially himself in 1527 and 1533, incorporated into a version of Erasmus's Cato. It may very well be that Bade left off printing his own commentary as a separate out of admiration for the version of Erasmus, which Bade published in 1515, soon after its first appearance, and which he continued to print right up to his death. (99)

NOTES Open Bibliography (330 KB pdf) (90)Â Gehl 1993, 109-122; Baldzuhn 2006, 34-40. See also sections 4.01 and 402. (91)Â Baldzuhn 2006, 354. (92)Â Glauche 1970; Gehl 1993, 13, 114. (93)Â Blasio 2005, 15. Black 2007, 123-126, recognizes the combination as "a standard duo" for basic reading instruction in fourteenth-century Tuscany; but elsewhere (46, 110) treats the Cato as a reading text in the elementary Latin course, especially in the late fifteenth century. It seems more logical to me to see both texts as one highly traditional and conservatively preserved unit across the whole manuscript period, adopted as such by printers from the fourteen seventies on. (94)Â Pseudo-Donatus 1500b, GW9014; the only recorded copy is at the Newberry Library, Chicago. (95)Â fol. b8r: Marci Catonis viri singularis ad vitam adolescentulorum liberis artibus instruendam utriusque virtutis felicissima instituta. (96)Â Pseudo Donatus 1496; GW 9027, IGI 3562. (97)Â Mancinelli 1518. It survives in this form in many libraries, sometimes with a general title page for the whole set; see section 3.16. (98) Pseudo-Donatus 1548 prints the distichs in the usual large gothic type but also provides thematic notes in the margin in minuscule roman type. On commonplace and paraphrase: Ong 1977, 147-181; Grafton and Jardine 1986, 22-25; Grendler 1989, 194-201; Moss 1999, 148-154; Frazier 2005, 192-202. (99) Renouard 1908 ii, 264-267; on Bade's commentaries, Schmidt 1975, 67-70; on the Sylvae, Crane 2005, 29-35. On Bade and Erasmus, Vanautgaerden 2008, 89-11, 200-213, 229-232.