1.08 Less Than Folio

Terence in folio was so standardized a format that we can discern a single design tradition in Italy across the entire period from the invention of printing to the middle of the seventeenth century. Small-format Terences varied much more. The Aldine press set a pattern for printing classical poets in octavo without commentary. But while some publishers mimicked the Aldines slavishly, others felt free to offer small volumes on other models.

Quarto Terences were common in France and England and normal in Spain and the Netherlands but never became usual in Italy. (41) The rare examples tend to be fat volumes that include the six plays with some or all of the commentaries usual in folio editions. As such, they were offered for the teacher's market or for advanced student use, and so they competed directly with the more common folio Terences. Given the limited margins of the usual Italian small quarto, however, the form would have proved less useful for a reader who wanted to annotate the plays, a factor that no doubt induced printers to continue to favor folio formats for Terence.

We may discern three distinct periods at which Italian printers experimented with presenting Terence in quarto. In the early fourteen seventies, a few large quartos were offered, especially at Rome, as an alternative to the folios without commentary. Alessandro Paganino produced an experimental quarto Terence in 1526 as part of a textbook series. And in the fifteen forties and fifties, a few further experiments in quarto were attempted at Venice. The only one of these latter to be reprinted was the bilingual Terence of Giovanni Fabrini, which will concern us later as an experiment in editing and translation. The fifteenth century quartos were made on very large paper so they

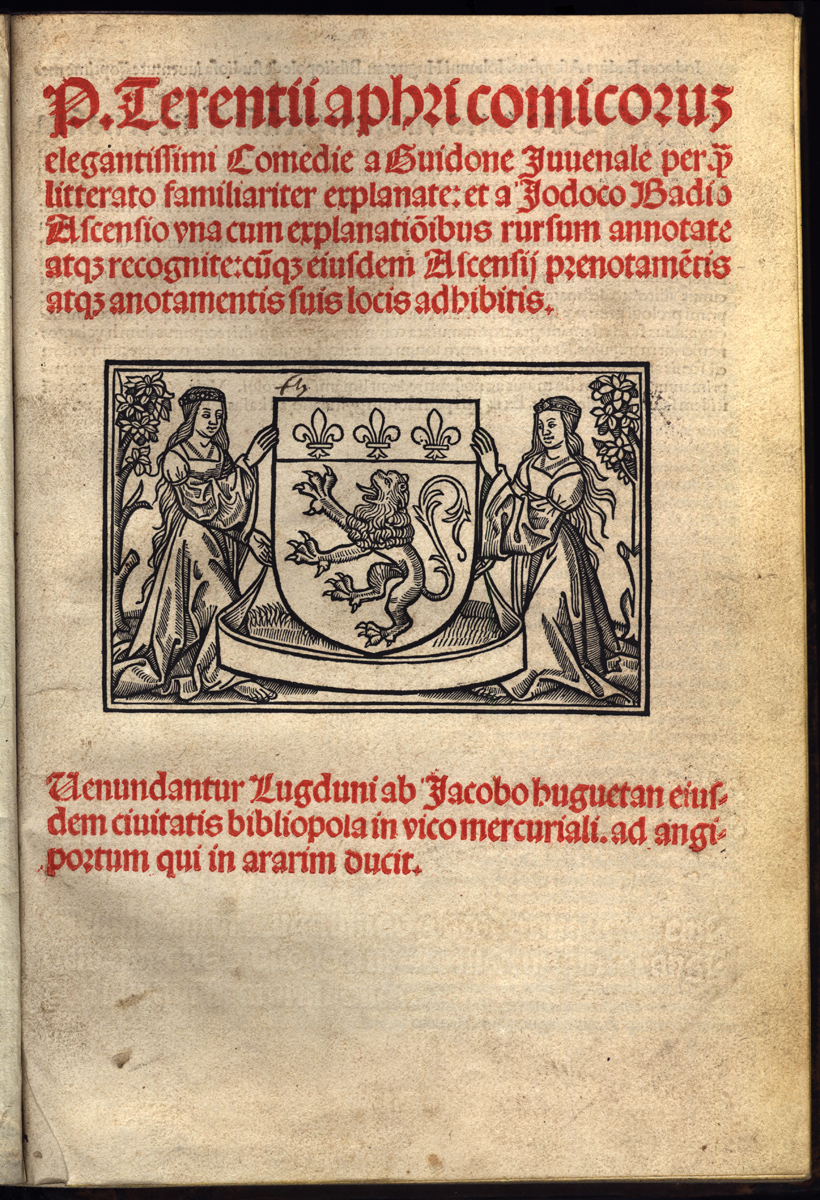

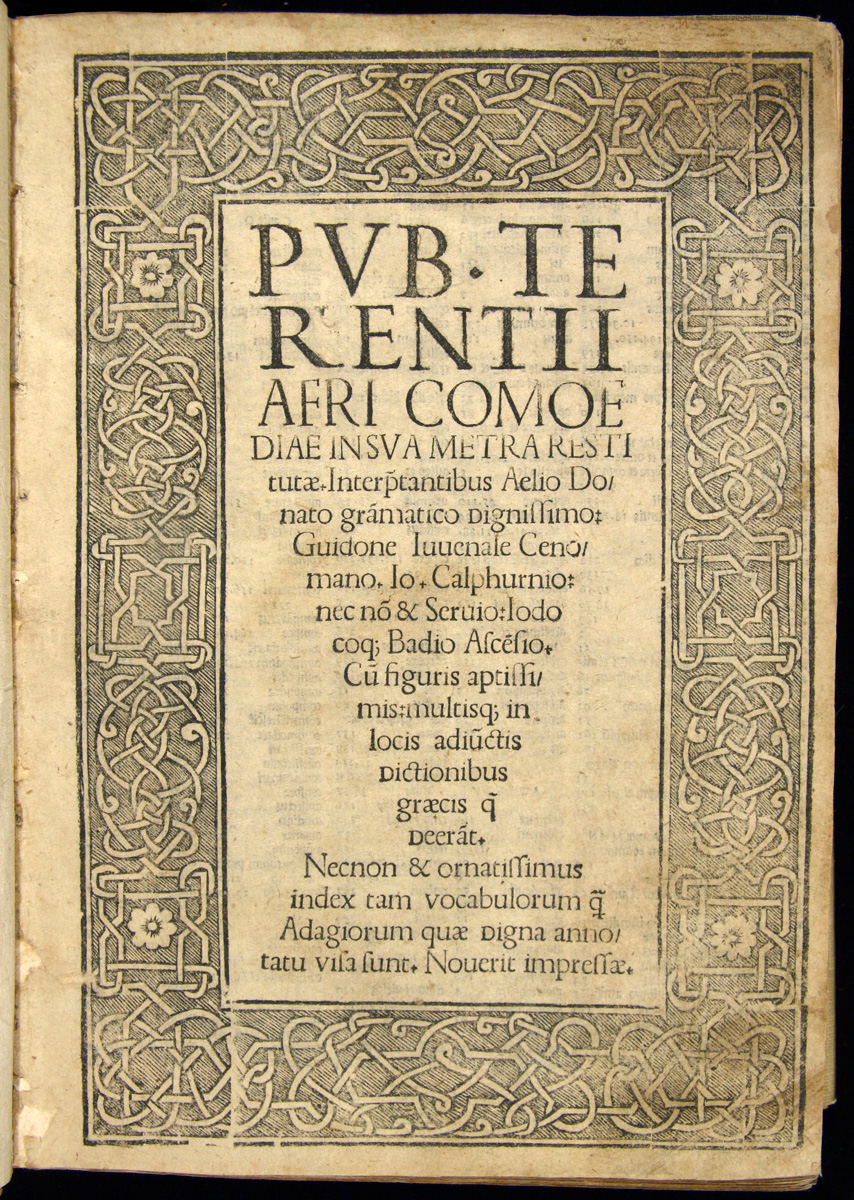

The 1526 Terence printed by Alessandro Paganino at Toscolano, exemplifies the design problems a printer faced in offering Terence with commentary in smaller quarto form. It is an ambitious volume, if somewhat backward-looking. (43) It opens promisingly enough with a typographically sophisticated title page. The handsome roman title is surrounded by a broad white-on-gray interlace border of a sort that was used repeatedly by Paganino for quarto textbooks in Latin. There are almost 300 folios numbered in roman numerals and the layout of the whole follows the folio Terences of the time in displaying the base text in a window on each page, so the double-page spread has two small windows entirely surrounded by commentary. Marginal index notes are an aid to reading, but they are squeezed rather tightly into the small space available. There are five commentaries, so Paganino was marketing to the humanist schoolmasters of Italy and their most advanced stud

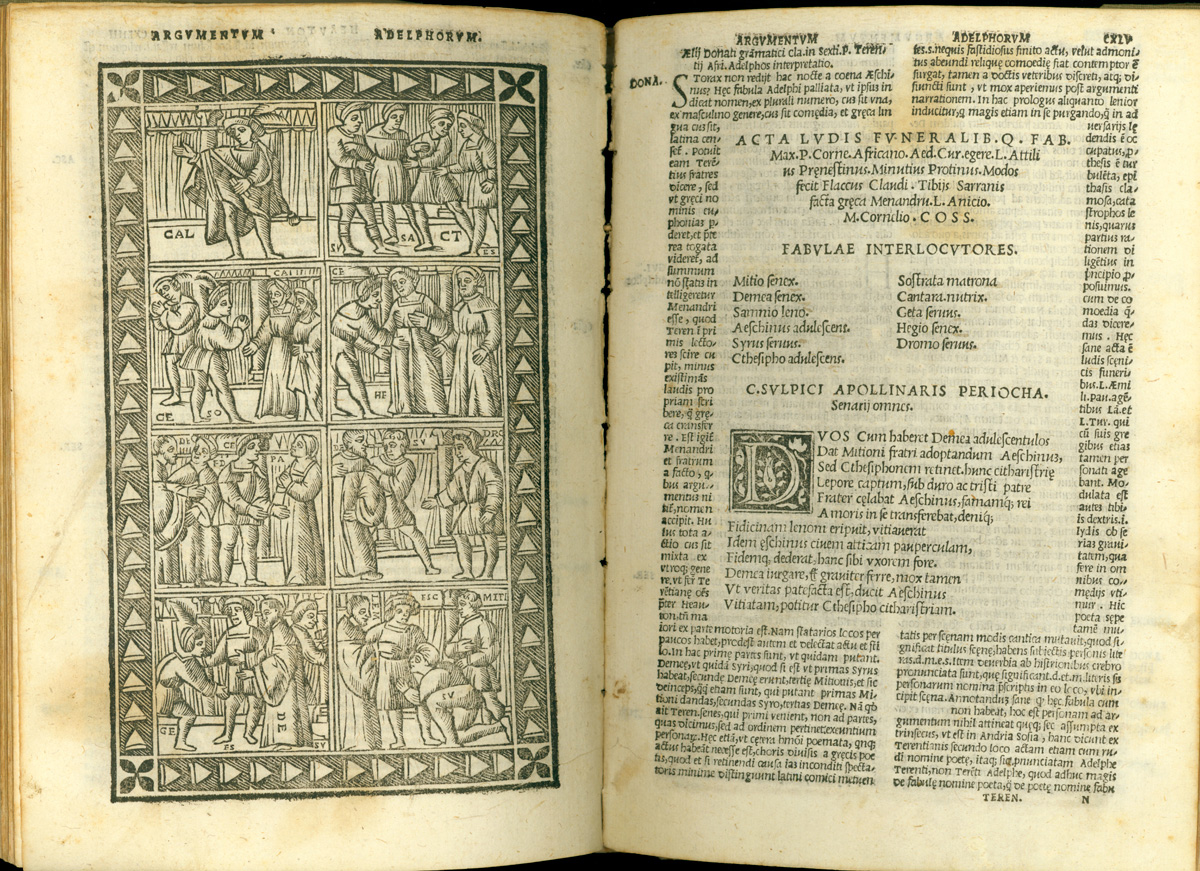

Paganino made one other innovation in his 1526 quarto, commissioning new copies of the Tacuino comic-strip illustrations in a form appropriate for a quarto volume. Tacuino had arranged the scenes four across in two rows at the top of the page that opened each play. Paganino had the very same eight scenes per play copied onto a full-page woodcut with two frames in each of four rows. This scheme created a handsome page to act as a frontispiece for each of the plays. Like the Tacuino strips, Paganino's were more decorative than useful, but they did fit the quarto format nicely and relieved the overall effect of the crowded text pages.

There were hundreds of octavo editions of Terence in the sixteenth century. The recorded quartos, however, are few, and all are Venetian imprints. After Paganino in 1526, only Girolomo Scotto in 1549, Giovanni Andrea Valvassore in 1550, and Vincenzo Valgrisi in 1558 experimented with the quarto format for the standard Terence with commentaries. We might well ask why Terence was never published in Italy after 1480 in a spacious quarto without commentary. This form was normal for all kinds of classical and contemporary poetry before Aldo Manuzio offered his popular octavos, and it continued to be used for many kinds of poetry well into the sixteenth century. The simplest answer is probably that the Aldine octavo swept competitors for this kind of book from the market for classical poetry. In the case of Terence, the strong tradition of folio Terences with and without commentary no doubt also contributed to the limited demand for other formats. (44)

NOTES Open Bibliography (330 KB pdf) (41) Lawton 1926, 284. (42) Lawton 1926, 283-286. (43) It is (according to the title page) a second printing, but no earlier one by Paganino in this format survives. The title page might refer to a 24mo Paganino of 1516 that survives in a single copy, but the note noviter impressae and the fact that this edition lacks a dedication present in the 1516 book suggests that there actually was an earlier printing in this format. Paganino had pioneered the use of such quartos for other Latin textbooks in 1522; see Nuovo 1990, 53-55, 83-89, 161, 185. (44) Kallendorf 1999, 46-50.